Year: 2000

Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami, never a fan of conventionality, shocked the audience after receiving the 2000 Akira Kurosawa Award by promptly giving it away to honor actor Behrouz Vossoughi.

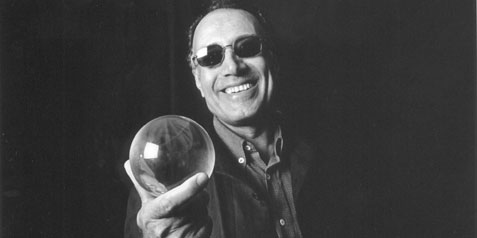

Photo: Director Abbas Kiarostami, recipient of the Akira Kurosawa Award, poses with his trophy at the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival in 2000. Photo by Pamela Gentile.

GREAT MOMENTS

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI: THE DIRECTOR BEHIND DARK GLASSES

By Maria Komodore

The audience in the packed theater rose and clapped enthusiastically as Peter Scarlet, the Festival’s artistic director, welcomed Abbas Kiarostami on stage to receive the Akira Kurosawa Award at the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival.

Kiarostami thanked Scarlet for the award, and paid homage to Akira Kurosawa: “I want to let Peter know how much I appreciate his award because of the name of Kurosawa and the kindness he showed me during his lifetime. I want to thank Kurosawa in his absence.” To the surprise of all assembled, he suddenly announced, “I would like to give this prize . . . to Behrouz Vossoughi,” the once famed Iranian actor who fled his home country for the United States in 1978. Before Kiarostami’s interpreter had a chance to translate his announcement to English, the audience, populated with Iranian Americans, burst in applause as the actor joined Kiarostami on stage.

While offering the award to Vossoughi, Kiarostami explained, “This is an award for all the years he worked in the cinema in Iran and for all the years he’s awaited work here in this country. I look forward to his return to the cinema.”

“I want to thank Abbas. He took me by surprise” Vossoughi responded. “As you know, he is a filmmaker who is in the world class and I am looking forward to the day when the Kiarostami Award will be awarded to other filmmakers.”

Abbas Kiarostami, while not a household name like previous Kurosawa Award recipients Arthur Penn or Joseph L. Mankiewicz, fell in line with the award’s tradition of honoring international masters with a rebellious spirit (like Ousmane Sembène and Arturo Ripstein).“In some ways, Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami is the stereotypical candidate for the Film Festival’s Akira Kurosawa Award for lifetime achievement in film directing,” Frako Loden wrote in SF Weekly. “He’s from a country with ‘issues’ with the U.S., whose movie industry is only beginning to be recognized by the West; his films are doggedly humanist, with an interest in children and rural settings, but framed by knowing self reflexivity; and helpfully, Kurosawa himself has expressed his approval.”

Born in Tehran in 1940, Abbas Kiarostami studied painting at Tehran University and in 1969 helped to found the cinema department at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults. His career as a filmmaker began in the ’70s with The Bread and the Alley. Of this film, the San Francisco Examiner’s Judy Stone wrote, “Made with nonprofessional actors, it indicated the elements that would characterize Kiarostami’s future work: improvised performances, documentary elements and real life rhythms.”

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s Kiarostami had a prolific output. An extraordinary sense of humanism prevails in his films. By using nonprofessional actors and shooting in rural areas, Kiarostami crafts deceptively complex stories that reveal the lives of everyday people and their struggles. Conflicts in his films often arise from the tensions between societal and religious constructs that dominate peoples’ lives and the will of the individual.

His first feature, The Traveler tells the story of a young boy who sets off on a journey to watch his favorite soccer team play in Tehran. Where Is the Friend’s Home?, his third feature, screened at the Locarno International Film Festival, where it won the Bronze Leopard award. According to Stone, this was the film that ignited international interest in Kiarostami’s work. Praise for his films “had begun to be expressed internationally in 1989 after the eight-year Iran-Iraq war when the Locarno Festival introduced his third dramatic feature, Where Is the Friend’s Home?” In it, Ahmad decides to go find his friend’s house in a neighboring village, despite his parents’ orders not to, in order to give him a notebook. The film prizes duty and loyalty towards a fellow human being above social roles and expectations.

And Life Goes On, which won the Roberto Rossellini Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1992, offers a self-reflexive glimpse on Kiarostami, and his own interest in actors as the main character is a director who visits the location of a previous film in search for his protagonists after an earthquake. Close Up and Through The Olive Trees both deal with the difficulty of negotiating the differences between image and reality. The former, which blends staged scenes with documentary footage, follows the trial of a man who posed as the well-known Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, in an attempt to convince a family to give him money for a film. Through The Olive Trees revolves around the relationship between an Iranian girl and a filmmaker. While acting in a film the girl refuses to communicate with the director because she feels insulted after he proposes to marry her.

In an interview with Cinema Scope, Kiarostami responds to a question about the element of repetition in his films. “Repetition is an illusion. In reality, things change. I would like to draw attention to the fact that what seems to be a cyclical thing is in fact a process of slow transformation and change. There is an audience who would get enervated and aggravated by this kind of reference to repetition in my work. This is an audience corrupted by a remote-control approach to filmmaking.”

Though he had a prodigious output from the late 1970s to the 1990s (directing 27 films in about 30 years), Kiarostami and other members of the so-called Iranian New Wave like Mohsen Makhmalbaf (A Moment of Innocence, SFIFF 1997) and Jafar Panahi (The Circle, SFIFF 2001) did not receive universal acclaim for their work (often censored in their homeland) until the mid-1990s. In 1997, Kiarostami won the Palme d’Or at Cannes Film Festival for his film A Taste of Cherry. As Jonathan Curiel wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle: “When Film Comment magazine asked a panel of experts to name the person in the movie industry who best defined the 1990s, the director singled out most often was Abbas Kiarostami.”

Despite the fact that many of his films have been banned by Iran’s government, Kiarostami does not have an embittered view of censorship. In the Q&A session that followed his award ceremony, a member of the audience asked him whether censorship had influenced his films. Kiarostami replied, “Censorship or not, my work speaks for itself. I also feel that the word censorship sometimes provides a shield behind which we can hide our deficiencies and absolve ourselves of our responsibility towards our work.”

A member of the audience asked the rather vague question, “Does the film believe in the Koran or existentialism?” Kiarostami, famous for his insistence on leaving his films open to the audience’s interpretation, replied, “I do not give answers. I give you information. I present certain things and it’s up to you to conclude what you will.”

After responding to many questions from the inquisitive audience, Kiarostami jokingly commented, “I remember in the past I used to have to first take tests and then be given an award for doing well. But in this place I was given the award first and now I’m being given the test.” Kiarostami politely requested that the Q&A be cut short so he could make a few remarks about his film. Proceeding with yet another joke, Kiarostami ribbed, “I want to empathize with those who didn’t enjoy the film. Truly this is how I feel myself. A lady who had seen [this film, The Wind Will Carry Us,] said, ‘Oh! I didn’t like the film. Why did you make it? I liked A Taste of Cherry a lot.’ I replied, ‘Well, you didn’t say that when you saw A Taste of Cherry.’”

“This is not a cinema that one relates to immediately,” Kiarostami conceded at the end of his Q&A. “It takes time for our feelings and responses to be able to come into place, to be able to come into play. And I’m certain that even if you didn’t like the film, you won’t forget it and this is to me more valuable than you liking it immediately.”